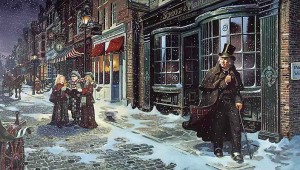

It is amazing that Charles Dickens, an Englishman, should be the author to give birth to the tradition of a white Christmas. Meteorological records do exist in England in the 19th century when Dickens was writing, and they reveal a fascinating statistic. According to these records, it snowed on Christmas Eve or Christmas Day in England an average of only one time every thirty-two years. Since Dickens died when he was 58 years old, according to the statistics he should have enjoyed no more than two white Christmases—and maybe just one—during his lifetime.

It is amazing that Charles Dickens, an Englishman, should be the author to give birth to the tradition of a white Christmas. Meteorological records do exist in England in the 19th century when Dickens was writing, and they reveal a fascinating statistic. According to these records, it snowed on Christmas Eve or Christmas Day in England an average of only one time every thirty-two years. Since Dickens died when he was 58 years old, according to the statistics he should have enjoyed no more than two white Christmases—and maybe just one—during his lifetime.

But the weather statistics tell us one other relevant fact. A tremendous volcanic explosion in the early 1800s so disrupted prevailing weather patterns and lowered world temperatures that it snowed in England on Christmas Eve or Christmas Day in 1816, in 1818, and again in 1819 and 1821; after that date, the normal weather patterns returned, and there was no white Christmas again until 1858. Because Dickens was born in 1812, he happened to enjoy a white Christmas when he was four, six, seven and nine years old— the very years when creative minds are most impressionable. Thus, Dickens was the perfect author to give us our first white Christmas. It should give us pause to realize that Bing Crosby’s greatest hit may owe its inception to a 19th-century volcanic eruption!

Perhaps the most significant change that Dickens made to Christmas traditions concerns the writing of the Christmas story itself. We have come to expect from Dickens the heavy doses of sentimentality which he liberally uses to underscore his usual themes of social injustice, mistreated children, and institutional abuses. But A Christmas Carol does not begin with the typical Dickensian heart-wringing prose. Far from it. Instead, Dickens composed his opening sentences to shock his Victorian readers: “Marley was dead to begin with. There is no doubt whatever about that… Old Marley was dead as a door-nail.” This is the “greatest expression of the Christmas spirit in the English language?” When the public first read these strange words in 1843, they were stunned that any author would dare to open a Christmas story with such a seemingly inappropriate tone.

But Dickens knew what he was doing, and what he was doing was single-handedly saving the genre of the Christmas tale from extinction. Before A Christmas Carol was written, all Christmas stories seemed to be so cloyingly sweet and vapid that the tradition of the holiday tale was in danger of being berated or ignored by literate people everywhere. Dickens decided that he must give new life to this endangered type of story by marrying it to its most opposite kind of fiction—the tale of terror. The full title of this book is A Christmas Carol in Prose: Being A Ghost Story of Christmas. With stunning originality, Dickens created Ebenezer Scrooge as a sinner so unrepentant that, if he were to have any hope of salvation, he would need the literal hell scared out of him. And then Dickens invented the four ghosts who could do just that. Both Marley and the Ghost of Christmas Yet To Come are so hideous in conception that they could have shuffled directly out of the pages of the cheap magazine tales of horror which Dickens devoured as a child (“penny dreadfuls,” Dickens called them).

More to the point, when Dickens was only three years old, his parents had living in the house with the family a woman from the streets who was supposed to help with domestic chores. It was her duty to tuck little Dickens into bed each night. Her remarkable talent for telling chilling tales of terror kept Dickens sleepless and spellbound. The little child’s favorite story was the tale of Captain Murderer, a handsome rogue who loved to invite beautiful girls to his house for a “dinner date.” These girls would discover all too late that they were not only his date but his dinner as well! Such stories made a lasting impression on Dickens which he would transform years later into his unique Christmas horror story.

Yet, with almost 175 years having now passed since A Christmas Carol was first published, some of its macabre surprises have evaporated in the interim. Take, for example, the famous phrase quoted above concerning Marley’s being “dead as a door nail.” Dickens mentions this fact not once but four times in the opening section of his story. Why this undue emphasis? Because there is a delightful joke hidden within the somber phrase which Dickens’ original readers enjoyed but which we no longer can understand.

What is a door-nail, anyway? Everyone knew in Dickens’ day, because almost everyone had one. The door-nail was a special nail with an enormous head, driven into front doors. The heavy brass door-knocker would then rest upon this nail. The iron door-nail provided two functions: protecting the door from the blows of the heavy knocker, and reverberating the sound of the knocks so those inside could hear them from any location in the house. Dickens’ age could think of nothing more dead than an object which had its head constantly bashed in by a knocker. The simile was alive to them.

Charles Dickens, though, saw all such cliches as dead, so he decided to reanimate this one with his own word-play. Marley, of course, isn’t “dead” at all, since early in the story he reappears to Scrooge. And when does Scrooge first suspect that his dead partner may once more be among the living? He makes the discovery when he glances at the door knocker and door-nail of his own front door when he returns home on Christmas Eve and sees them, to his horror, turn into Marley’s living face. So old Marley is as dead as a door-nail—because on this particular night the door-nail isn’t dead at all.

So much good was released into the world by this one short story that even William Makepeace Thackeray, a man who would later become Dickens’ greatest literary rival, remarked that Dickens’ masterpiece should be seen as a personal blessing on all who were fortunate enough to read it. Blessings seemed to flow from the story. When a magazine editor once asked Charles Dickens who he felt became more blessed by his tale—the man who wrote it, the public who read it, or the publisher who profited from it—Dickens’ answer summed up his feelings on the specific question and on the human race in general: “God bless us, every one!”